WALKING HARRY

“Summer of love, my ass.”

Tessa Scott cursed as she tore at the silver paper. Jerking her body sideways to protect her spotless white bell-bottoms, she angled a softened Hershey bar into her mouth. She readjusted the strap on her shoulder bag. It was a big yellow leather thing, a Salvation Army find. Buttery soft, it was like nothing she had ever owned. It carried all she held dear: lined notebook—black cover, red binding—spiral-bound sketchbook, favorite pens—her precious Montblanc—and a few felt-tip markers. Slotted inside, at least two of the many books she had going at any time: Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem and Revolution For the Hell of It by the self-professed “nosy Jew-boy,” Abbie Hoffman. Some days Tessa leaned toward the cool, spare non-judgmental tone of Didion. On others she faced life with Abbie, raw-knuckled and ready for a fight. At the bottom of her bag was a green-and-gold pack of Dunhill menthols. In among the cigarettes she could hardly afford, a freshly rolled joint.

It was the middle of August. Tessa had just turned twenty-three. There were still plenty of dog days ahead. Walking suited her, even as she tolerated the heat. She screwed her nose to the already exhausted early morning air. It reeked of rotting vegetables packed into metal trashcans awaiting pickup outside the markets on upper Broadway. This was her neighborhood, near Columbia University, where she’d sublet a studio apartment in June. Her bare arms glistened with perspiration. Already, New Yorkers were bitching about the demand for exact change on buses that would be enforced at the end of the month. Whenever she could save a couple of dimes, she walked. She’d already spent half the fare on the chocolate.

Tessa strode with purpose, avoiding the odorous proof of dogs deposited in the street. She was on her way to the East Side to pick up Harry. He was a wealthy man who required a walker. Tessa was the walker. High cheekbones supported her sleepy gaze. She had long, naturally blonde hair, and a headlight smile when she bothered to turn it on. Her favorite tight-fitting bellbottoms clung to her slender hips. A bright yellow-and-red sleeveless tie-dyed t-shirt tucked loosely into a wide patent leather belt. As soon as Tessa left Harry, the hem of her loose shirt would be gathered and knotted tightly, exposing her tanned midriff. Bangs that came to her fine eyebrows stuck to her satiny forehead. Her ponytail, defying humidity, swung jauntily in step with her determined pace. She knew she looked good.

“You remind me of Joni Mitchell,” Seth had said wistfully, before asking her to return the keys to their apartment on the Upper East Side.

She laughed out loud at an image of Seth, her soon-to-be ex, slithering nearly naked in acres of mud at some hippie fest, getting up to god knows what. At the crosswalk, an old woman alongside Tessa looked up bewildered. Tessa shrugged her shoulders in an I-can’t-help-it way.

Seth bitched that he’d missed out on the whole summer of love thing. He’d told Tessa the festival in Bethel would be a last fling before he settled into grown-up life. His old Ethical Culture buddies from the Fieldston School had gone along for the ride. They’d be gorging on sliders from White Castle, littering the dashboard and floor with grease-stained paper bags. The car’s interior, its floor gummed with soda, would be well seasoned with the aroma of fried onions, fat, cigarettes, and marijuana.

Seth was more likely to be one of the thousands stuck in traffic on a highway going nowhere. She pictured him arced like a jockey over the steering wheel of a platinum-colored El Dorado, that too-big car his father had leased for them. Seth, in his ratty navy-blue Lacoste polo, collar cocked purposefully. His clip-on sunglasses flipped like cartoon eyebrows.

That car had been an embarrassment, conspicuously nosing through uptown streets on a hunt for dime bags. The magic gas-guzzler would look ridiculous alongside psychedelic VW buses in the anti-establishment parade of laboring pickup trucks heading for Woodstock.

Tessa continued down Broadway, more optimistic than she had been at the start of the weekend. She was rescued from a weekend of recrimination, mostly self-directed. When she’d moaned about missing out on Woodstock—this could be history in the making—her old high school friend, Hugh, set her straight. “That’s rich white hippie shit,” he told her.

He packed her into the crowd pressed inside a ragged rectangle of green in Harlem. Mount Morris Park was ringed by Black Panthers, with thousands of others who had ignored the heat, disproving the cops’ prediction of another Newark, another Detroit. Instead of rioting, the laid-back crowd sucked on fat joints, grooving to Nina Simone. From the stage the singer demanded, “Are you ready, Black people?” The crowd whooped their assent. Hugh’s unaffected grin beamed like a pearly crescent in a dark sky. He squeezed Tessa’s eager white hand. She tightened her grip on his.

Hugh had not deserted her. Not when her father fled a failed antique repair business and an erratic wife, carting Tessa off to spend her senior year in Hartford, Connecticut, where they’d shared a cramped, furnished apartment on Laurel Street. Not when she’d confessed to Hugh a disastrous friendship in Hartford with a girl whose coarse complexion and ardent nature had spooked her. Not when she returned to Manhattan and shared an apartment on Perry Street with another former classmate who hadn’t been nearly the friend Hugh was. He and Tessa were still artists together. They haunted the galleries and museums as they had done as students at the High School of Art and Design. They took classes at the Art Students League. They sketched everywhere, excited by everything—until Tessa met Seth.

Hugh had been the unwitting matchmaker. When Tessa turned nineteen, Hugh introduced her to soul food and jazz. They went to Sylvia’s, a new restaurant in Harlem. They gorged on ham hocks, fried catfish, collard greens, and black-eyed peas.

After dinner, he walked her a few blocks to the Lenox Lounge to see a modern jazz quartet. Tessa was new to the genre. She fell quickly in love with the furious beat that both shocked and hypnotized her. The antics of a pack of over-stimulated white college boys seated near them distracted her. She leaned over to one who bore the bespectacled look of a mad scientist atop a footballer’s physique. Ever so politely, she told them to shut the fuck up. Seth was smitten. He abandoned his friends at the bar, and followed Tessa into the street after the gig. Ignoring Hugh, he pleaded for Tessa’s phone number.

Tessa and Seth were a bad fit from the start. The foreshocks only became apparent in hindsight, when their marriage crumbled from the earthquake it turned out to be. Infatuated by their differences—for her, his wealth and for him, the paucity of hers—their brief, drug-fueled affair resulted in pregnancy. The mother of Seth’s best friend arranged a clandestine abortion, much to Seth’s relief. Afterward, Tessa’s demeanor had been wrongly interpreted. She mourned something, but what it was had escaped her.

Tessa married Seth in Arlington, Virginia. Standing near the entrance to the Holland Tunnel, they had not waited long before they’d hitched a ride south. The driver, in a flagrant move, pegged them as a modern-day Bonnie and Clyde, revealing immediately that he was armed. Tessa bolted from the car, back to the curb. The man grinned. Said the gun was in the glove compartment. It was not loaded. Seth, annoyed, urged her back into the car. The driver leaned across Seth, popping the glove compartment. “Take a look at that, College Boy,” he said.

Perched in the back seat, like a watchful film extra, Tessa held her breath as Seth extracted a handgun, palming it under the driver’s watchful eye.

The driver directed Tessa to a cardboard carton filled with sawdust. At his urging she picked out a delicate bisque figurine. It was a miniature nude he called a “naughty.” Its skin was the color of peach ice cream. Tessa brought the six-inch figure closer for inspection. Its enigmatic expression defied cuteness.

The man bellowed above traffic as they sped southward, “Can you all believe that was shocking?”

“It’s beautiful,” Tessa murmured.

“She’s an innerestin’ collectible. Cheap in her time, but could be worth a lotta money.”

Seth gingerly replaced the handgun.

On the bus ride home the following day, Tessa had discovered that she’d lost the marriage certificate.

She veered east on Eighty-Sixth Street, thinking about Hugh. Though he had not said as much, she imagined he was overjoyed when she’d told him it was over with Seth. Her marriage was broken, but her friendship with Hugh remained intact. What he had said was true, though. She had retreated from a creative life. She had allowed herself to be callously tossed—an object of curiosity—among Seth’s family, his disapproving mother and her social circle. She was the girl from the projects, the outsider.

Seth’s family was loaded. He had grown up in a sprawling apartment on Fifth Avenue, never having had a summer job during his private schooling. He went to the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. Tessa had grown up in the Jacob Riis Projects on the Lower East Side. She worked summers throughout high school. Skipping college, she embraced the artist’s hardscrabble life. When they married, Tessa left her basement apartment on Perry Street. She moved with Seth to a brightly lit one-bedroom in a doorman building on the Upper East Side, close to the hospital where Seth would begin his medical degree. His father, a corporate attorney who had done well, paid the rent.

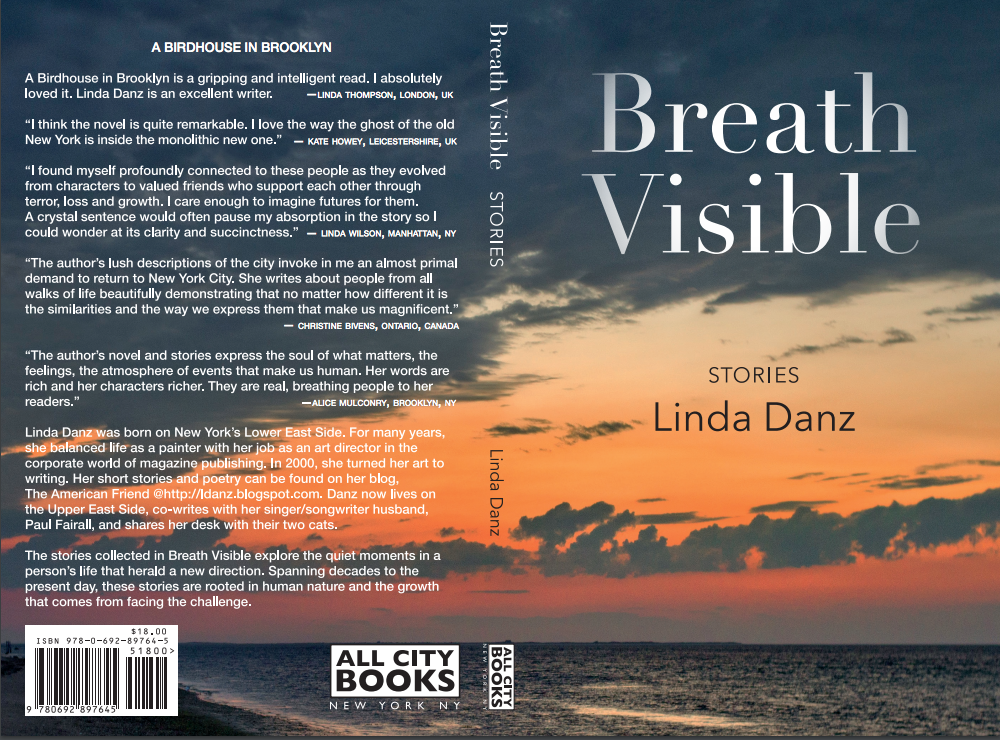

At first, Tessa strove for independence. She scoured the Village Voice classifieds for something different. She didn’t have to work. When she complained that his family looked down on her, Seth admonished her. “You’re just emphasizing the differences,” he said. “You don’t have to do this. Who is this guy Harry? Paint or something, or I don’t know, those woodcuts.”

Entering the park along the transverse, Tessa slowed her pace, enjoying the summer day. She loved Central Park and missed its closer proximity when she’d lived with Seth. She had more than enough time to get to Harry’s apartment on Park Avenue.

Tessa didn’t often get beyond the front hall—the foiyay, as his wife called it—since she’d answered an ad in the Village Voice. At her interview, in the luxurious, if dated, living room, Tessa was offered a cup of tea, which she accepted from the platinum-haired, carefully dressed woman who kept her eye on her husband. Harry stood near the grand piano, trembling slightly, staring straight ahead. Tessa guessed from the black-and-white photographs in gaudy silver frames displayed like awards across the grand piano, that Harry had been in entertainment. Harry’s doctor, a psychiatrist, asked Tessa if she felt she could handle Harry.

Tessa smiled at the twitching man gripping the piano. She stood up and took Harry’s arm.

“I think we’ll do just fine,” she said.

The doctor and Harry’s wife had exchanged glances. “You’re hired,” the doctor said. Tessa had shuddered a little at the mirthless grin buried in the doctor’s dense walrus mustache.

Harry was improving. In the past couple of months, at his request, they had walked more often. Apart from a few mystifying tremors, he was calmer. Harry was rediscovering speech. He and Tessa were able to hold conversations—many abstract, some a few more personal. His gait was steadier than it had been on their first outing.

Tessa thought the man he must have been was re-emerging. Tall, though slightly stooped to ingratiate himself and put one off guard, he was someone who had been used to running the show, whatever that show was. Harry might have been a flirt—surely a kibitzer.

After a few sessions, Tessa ruminated on how detached Harry’s wife seemed from her husband. She talked about him, not to him. He was less like a husband, more like a ward. Rarely stepping out of the character of a well-dressed mannequin, she sometimes displayed a fawning affection for Harry that made Tessa uneasy.

Tessa collected her pay at the psychiatrist’s office a few blocks north of Harry’s building. The doctor had no receptionist, which struck Tessa as strange. She rang. He buzzed her into a windowless outer room. A deep pile carpet, the color of sand, covered the floor of the nearly bare room. The walls matched the carpet. One large abstract print in desert pastels hung on the wall behind a fawn-colored leather wing chair—the lone chair in the room. If the doctor were unable to see her he’d leave a check in an envelope on its seat.

Tessa was always relieved when he was too busy to engage her. She felt shy and skittish around him, more so since the incident with Harry, when she’d taken him to see Roman Polanski’s new film, Rosemary’s Baby.

It was a stupid thing to do. She had been walking Harry for only a few weeks. When asked how their day had gone, Tessa usually mustered a cheery reply. “Fine,” or “Great!” She’d very nearly quit Harry after the first week. He shouted convulsively when she least expected it. Sometimes he’d stop dead in the street, fearful of crossing some invisible line. Tessa had to learn to wait patiently for his motor to shift gears. She usually gravitated to Central Park, where they spent most of the time sitting on a park bench. Children were frightened of him. She’d watch Harry as he trembled a hot dog into his mouth, sauerkraut raining onto his lap. Once they had visited the Central Park Zoo. They’d both been sad afterwards.

But on a dreary day, just after a rainstorm in early spring, Tessa had been at a loss. Park benches were pooled with rain. In just a few weeks, they’d exhausted the museums closer to home. Everyone was talking about the new Polanski film. If they sat in the balcony for an early afternoon screening, perhaps they would disturb no one. Harry might even fall asleep.

As it turned out, the doctor in the film who terrorized Mia Farrow’s character shared Harry’s psychiatrist’s surname. Harry grew visibly more agitated whenever Ralph Bellamy appeared on-screen in the role of the malevolent obstetrician. Tessa finally abandoned the film when she offered Harry popcorn. He began shouting unintelligibly, flailing his arms like a pinwheel in a storm.

Outside the theater, Tessa picked salty white buds from her hair. The rain had stopped. A glimmer of sunshine made her hustle him past the Plaza Hotel, into the park at Fifty-Ninth Street. She prodded an agitated Harry to an empty bench near the pond, trying to calm him down.

“Sapisfucking…tryna…fuck…fucking…trynakill—,” Harry bawled.

At a loss, Tessa shouted at him, “Stop it Harry. Stop it now!”

Like a mechanical toy at the end of its wind, he collapsed into silence beside her. “Harry,” she soothed, “the doctor is trying to help you. Your wife loves you. I’m here, Harry. No one is going to hurt you.”

She’d kept quiet about the failed expedition that had caused Harry’s outburst. Tessa had been warned not to overtax him, to keep to the park, stay off public transportation. Take a taxi if they had to, but best to stay close to home. She’d held his hand in the cab. Harry had been steadier by the time she’d dropped him off, almost tranquil. “Let sleeping dogs lie,” Tessa had reasoned.

The next time she picked up her pay at his office, Tessa noticed the doctor’s brass plaque was missing from the front of the building. She waited while he wrote out the check.

“Somebody steal your plaque?” she asked, making small talk.

He looked startled at first. Then came that expansive, off-putting laughter, brimful of gravity. “It’s a very interesting story actually. That film? Rosemary’s Baby?” He advised her not to see it. Tessa blushed deeply, shaking her head. “It’s rather gruesome, not for a young woman like yourself.”

“Have you seen it?” she asked.

No, it wasn’t his taste.

Tessa fidgeted nervously, anxious to leave and cash her check.

The doctor stared through her. “I’m telling you this in confidence, okay?”

“Okay,” Tessa replied. She listened restively as he told her about his odd connection to the Polanski film.

“The author of the book had a gripe against me. Seems I was treating his girlfriend at the time. He called me. He was livid with accusation. I was trying to drive her insane. I would kill her. I was evil. I had to be stopped. I’ve decided to drop my lawsuit. Better for my patients. I don’t know if he is still with her.”

He stopped to gauge Tessa’s reaction. She remained politely poker-faced.

“She’s no longer a patient.”

He lowered his eyelids, throwing his head back. A silent minute passed, compounding Tessa’s unease. Just as Tessa was about to speak, to tell him she had somewhere else to be, he jerked forward.

“This character, this doctor in the movie, is his revenge.” He reached across the desk, her check in his outstretched hand. “Pathetic.”

Tessa shuddered at the memory as she exited the park onto Fifth Avenue. The doctor was a strange guy, but he was looking out for Harry. She’d keep the office visits short.

The Metropolitan Museum stretched downtown. Tessa wasn’t sure what was on special exhibit, but they could wander the period rooms, have a bite in the cafeteria. She loved eating off a tray at the little tables that surrounded the reflecting pool. At the far end stood the smiling Etruscans. She and Harry guessed at punch lines to the sculptures’ ancient jokes.

They had not been back since the spring. That an extensive exhibition like Harlem On My Mind would be too much for Harry had been a possibility, though it had merely tired him. Throughout, he’d been alert and communicative, especially in the rooms devoted to the 1930s. He paused at practically every photograph, scrutinizing as if for clues. They stood silently and watched a video of a former slave who lived in Harlem. Harry had not taken his eyes off the woman.

When they returned, Harry’s wife was incredulous. “Why would you take him there?” she asked.

Harry stuttered a retort for the first time since they’d begun their outings. “I-I-I wanted to go.”

“But it’s awful,” his wife said, nonplussed. “What he’s done to the façade. It looks like a fire sale, that ridiculous sheet hanging there.” She nervously patted Harry’s arm and called for the maid. “Tom’s up to his old tricks, I fear.” She spoke of Thomas Hoving as if he were a friend, which he probably was. “It’s too confrontational,” she sniffed. Tessa had read the newspaper article calling the exhibition irrelevant. Calling Negroes irrelevant. She didn’t understand.

Harry had responded as he’d been led away, catching his wife off guard. “It’s s-s-supposed to be.” Tessa had registered something like shock creeping into his wife’s expression.

Tessa crossed Fifth Avenue. Harry’s apartment building was just up ahead on Eighty-Third at Park Avenue. She looked forward to seeing Harry in his now customary seersucker suit, always with a club tie and a pastel-colored shirt. He’d started wearing a yellowed straw hat with a broad brown grosgrain ribbon, tipped at a rakish angle.

His wife had fussed when it first appeared. “That old thing,” she said.

The doorman at Harry’s building greeted Tessa, calling her “Miss.” She was early and knew not to show up before the appointed hour. “I’ll just sit for a few minutes,” she said, breezing into the elegant flower-bedecked lobby that stretched like one of the great halls in the Metropolitan Museum. She settled onto an upholstered bench near the elevators. Her flushed appearance drew another smile from the white-gloved elevator operator.

Tessa fanned the pages of Abbie Hoffman’s book. She felt a wave of unease. Maybe it was the gory details about the Manson murders played out in the tabloids, or the whole Polanski thing all over again. Maybe it was too damned hot. Nowadays Harry was ready and waiting for her no matter the weather. They’d used to go to Soup Burg on Madison, which Harry liked, but his wife disapproved of what she called greasy spoons. “You’ve seen p-p-plenty,” Harry said. His wife had checked her expression, responding blithely, “Well, as you can see Tessa, he’s still got his imagination intact.”

Maybe they’d take a cab to Serendipity. Apple pie for Harry; she’d order a chef’s salad and a frozen hot chocolate. They could still catch a movie. The Odd Couple was sure to be harmless fare. Her job was getting easier, the perks growing.

Harry had asked if she liked walking with him. Of course she did. Then he told her that he pretended to be crazy at home just to keep up the walks with her. Tessa had been terribly moved by that. She wondered how long before she could get Harry on the Staten Island Ferry. How long it would be before he would tell her about himself, his past. How long before they could step out of the still constricting present.

The week before, Tessa had ventured to ask the doctor how she was doing. She had long-range dreams, both for Harry and herself.

“Well,” he said. And then, inexplicably, he’d added, “A little too well.” Of course he was kidding her, he’d added.

When she entered the apartment, the light was the first thing Tessa noticed. Until that morning, the living room had always been shrouded in heavy, olive-green velvet drapery. Massive oak furniture had disappeared in the darkened room. Now the room glowed with sunlight from bare windows. The walls had been stripped of paint. The claret-colored carpet had been removed from the foyer, exposing a veined white marble floor. Paint samples in shades of ivory and beige were taped to the walls. Tessa saw the piano covered in plastic sheeting, the photographs removed. She waited in the foyer as the maid instructed until Harry’s doctor appeared.

“We won’t be needing you any longer,” he said. He handed her a check. “Thank you for everything. You’ve been most helpful.”

“Harry…?” Tessa managed. Her confusion only grew when he prodded her to the front door.

“Unfortunate,” is all he said. “Most unfortunate.”

Tessa stood for a moment in front of Harry’s building. “Well, that was weird,” she muttered. The doorman stared straight ahead.

What next, she wondered. Hugh would say, “No excuses now, girl.” She could finally lay siege to her life in cartons. Liberate her few possessions once and for all. Seth had let her take the stereo. He was getting a better one anyway. He’d said that in the offhand manner he’d affected since they had agreed to divorce. There was a new album Hugh had given her called Karma, by some way-out sax player named Pharaoh Sanders. There was a joint in her bag. When she got back to the sublet she’d dig out her woodcutting tools. She’d sharpen them slowly and carefully on a whetstone. With a brush loaded with India ink, she’d commit her thoughts to paper. When she was satisfied, she would transfer the ink drawing. Then she would ravage a clean block of pine with chisels and Japanese knives until the image it bore resembled her conviction.

Tessa started back toward the park. Walking suited her. She was not a collectible.