“I’ve got some good saints out there—

that’s right—that pray for me constantly.

You’ve gotta have that! You do.” Whitney Houston

that’s right—that pray for me constantly.

You’ve gotta have that! You do.” Whitney Houston

SAINTS AND ANGELS

“Weeya-a-al-liv

in a yellow subway car, a yellow subway car, a ya-a-alow subway car. Weeya-a-al-liv—c’mon

pe-e-eople. Sing!”

Dina

Frey is in no mood for the teenager prancing through the subway car like some

hopped up bantamweight. She takes in the braided woolen pigtails flapping from

a colorful knitted cap pulled low over the girl’s ash blonde dreads. An unzipped

parka slides from her plumpish frame revealing a tee shirt that says: Beaches are hotter in LA. Other

passengers—veteran riders in winter coats slung open—simultaneously ogle and

ignore the fifteen-year-old.

Dancing

girl is in her underpants.

Dina

thought she’d left her old friend Gaby’s apartment late enough. She had hoped

to miss the onslaught of near naked riders on No Pants Sunday. By the time she’d

left 103rd Street and reached her place on East 2nd Street,

the pant less mob would be slapping each other’s butt in Union Square, falling

about in crapulous abandon, mugging for iPhones in competitive undress. This

girl was late for the party.

“And the ba-a-a-nd begins to play

Ev’ry one of us la-la-hey

Yellow suhmarine, yellow suhmarine

We all live in a yellow suhmarine

Yellow suhmarine, yellow suhmarine…”

Ev’ry one of us la-la-hey

Yellow suhmarine, yellow suhmarine

We all live in a yellow suhmarine

Yellow suhmarine, yellow suhmarine…”

A

squat, disheveled character boards at 96th Street. She is of

indeterminate age, roughly hewn. Her stiff outer clothing appears to be the

only thing keeping her upright. Her putty

colored face appears contorted against her will. She makes squinty eye contact

with the girl, putting an abrupt halt to the singer’s refrain before she

shuffles through the moving car, dully chanting her mantra, eluding hunger,

invoking the Divine: “Excuse me. Good afternoon.

Trying to get something to eat, spare change or a sandwich. Have a blessed day

and evening.”

Dina

pokes a dollar bill into a paper cup gripped in the woman’s small, grimy hand.

Ignoring

Dina, the woman rasps: “Enjoy your concert.” She heads toward the next car, her

expression that of one never having been heard.

“We-e-e…”

Dancing

girl hovers. At Dina’s silent reprimand the girl spins from the overhead

handrail like a planet that has lost its trajectory, falls backward, and is

gingerly steadied by another passenger.

No

harm done, Dina figures, sneaking a peek at the girl. She feels only slightly

sheepish at forcing a disquieted withdrawal. The girl’s friends huddle at the

end of the car. They don’t egg her on, nor do they attempt to stop her. One of

them guards a backpack, a jacket and sweat pants on an otherwise empty seat. They

are all fully dressed.

Dina

closes her eyes, leans back and remembers she’d read: “There’s something

delicious about finding fault with someone.” It is Dina’s nearly constant

quest, to rise above things. Not like her

sister, Sandra Grace, whom she had not thought of for years and who is back

hogging Dina’s frame of reference. Thanks to a phone call the night before from

her sister’s son, Garth, Dina’s 44-year-old nephew. He’d managed his escape at

the ripe old age of fifteen, petitioned the courts, and got himself fostered.

“She-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named

is gettin’ married,” he drawled. “This’d be what, Aunt Dina, husband number

four?” Four? Even Dina was unsure. It was not worth thinking about.

The

red-faced girl is, at least in Dina’s opinion, some kind of brave. Unlike other

riders, gormless, earbud zombies who, almost to a one, vibrate to an inaudible

beat, stare into some intangible distraction, or slide practiced fingers across

little screens on hand held devices.

Dina was audacious, but age empowered a more

considered approach. She is public housing stock; product of an infuriating, erratic

mother, whose moods she’d struggled to keep up with and a father who was a

reluctant traveler, at best.

Dina is pale, petite and fine-boned, deceptively

fragile. Her once long and lustrous raven hair is still long. She outwits the

gray and keeps it dark, often swept up in a ponytail or braided down her back,

but it is thinner now. Dina hates getting older, just hates it. These days, in

the wrong light, which is nearly every stage light that blinds her, and with

the wrong camera, which is every cruel digital result posted on the Internet; she

looked like Iggy Pop in drag. She is a lot prettier in person. Her sister, Sandra

Grace, was in every fiber of her being the opposite of Dina—blonde, full bodied,

girly and angry; except the laugh. That they share with a vengeance.

In

the summer of her fifteenth year,

Dina Frey was in a girl gang in Astoria, where she grew up. They were the

Angels, self-appointed groupies who followed her dad’s drum and bugle corps. Stalked,

more like. The band was called The Saints. The boys had cool jackets of thick,

black, felt-like wool. The band logo swept across the back of the jacket like

the pearly lip of a wave on a dark sea. First names were stitched on the front

in elegant cursive under the emblem of the Veterans Of Foreign Wars. Her gang

had black jackets, too, but the cheap cotton kind they’d embroidered

themselves. Tricia lusted after Louie, the loveable and dull witted bass

drummer. Angie dogged the cymbal player, who, like her, was height-challenged.

Dina favored the lanky, stoop shouldered snare drummer called Irish. Skanky

Sharon had a thing for buglers—the entire horn section, in fact. Dina quit

when they hid razor blades in their bird nest hair and challenged the Catholic schoolgirls.

She had been in it for the boys and the jacket. It didn’t fit with her new life

at the High School of Music & Art. Her spiteful, younger sister had taken a

pair of scissors to the jacket.

Dina

lets her gaze drift around the subway car, seeking distraction.

She

guesses the older, white haired couple that boards at 86th Street are

tourists from their frozen, non-committal smiles, sensible walking shoes and

the zoom lens on expensive digital cameras in hand, ready to capture urban

wildlife.

A

man hops in as the doors close. He is dressed in tight, rust-colored trousers

pegged at the ankles and holds a carryall emblazoned with the name of some

hotel in Williamsburg. An orange-beaded mala bracelet encircles his delicate

wrist. Tortoise-shell sunglasses hang from his neck on a thin gold chain. He stands,

rigid, against the door ignoring the girl. Dina suspects he doesn’t notice

anyone in the car. Suddenly, she wonders: There’s a hotel in Williamsburg?

At

77th Street Dina slides over to make room for another woman, a Black

woman, carefully turned out in her church-going coat and matching rose-colored

hat. She carries a pocket-sized Bible with a white leather cover. Dina guesses

they are nearer the same side of sixty-five, the far side.

“People!

Sing! We-e-e…”

Next

to Dina, the woman makes a low, clucking sound with her tongue. She nudges Dina

and they exchange the brief conspiratorial smile of provisional intimates. Across

the aisle twin girls press under their mama’s protective arms like wary chicks.

With wide-eyed scrutiny they sneak glances, through bangs of multi-colored

beaded braids, at the gamboling white girl.

Resigned,

the girl finally returns to her friends, slender boys with dark, spikey hair

and marmoreal complexions. They could be gay. Hard to tell these days, which

was a good thing, Dina reasons. One of them helps bare legs into sweat pants, and

then hugs the girl like she’s won a marathon. Another useless event, Dina thinks,

half-expecting him to produce a shiny foil blanket.

She’d

spent the afternoon, on the Upper East Side, visiting Gaby Schaffert on her friend’s

birthday. Gaby was laid up from a fall that summer, which left her with skinned

knees, a broken front tooth and painfully uncooperative back and shoulder

muscles. During the visit Gaby took calls from three of her four sisters, a

cousin, and her mother in Switzerland. Dina listened, amused, aware of her own

diluted strain. Between calls, the women bitched laughingly.

“How

do we make those hipsters disappear, Dee?”

“Dunno,”

said Dina.

“Ask

Magic Man. Bet he can do it.”

“I

asked Stephen, Gaby. Even he can’t perform that trick.”

Responding

to Dina’s news from her nephew, Gaby rolled her eyes.

“He’s

speaking to her? He’s talking to the vitch?” After nearly forty years as a New

Yorker, Gaby’s Swiss German accent had not lost its edge.

“No.

That won’t happen, I’m sure. Someone he knows saw it on Facebook.”

Before

Gaby could ask: “We’ve blocked her.”

They

were longtime friends, had known each other since their early 20s when Gaby arrived from Switzerland to

attend the School of Visual Arts. They once lived on the same block where Dina

remained. Second Street, between B and C. They had seen their

neighborhood—burnt out buildings with blackened windows like toothless

maws—suffer the indignity of the city’s abnegation. Until squatters drifted in

like seeds on the wind and life began, again, to sprout from the wreckage.

But

the mid 80s brought unwanted attention from Hollywood. Avenue C was oddly transformed

into a movie set. The director, not content with reality, had built his own

tenement, a veneer that suited his vision. Debris was brought in by the

truckload and dumped in a vacant lot. Irony was not lost on the residents.

A

decade later, on a late spring morning,

in the neighborhood that was by then known as Loisada, helicopters

thundered above 13th Street like agitated birds, monstrous,

intimidating birds intent on raiding another’s nest. Resilient homesteaders had

battled for homes for the poor, for attention to be paid to the homeless and

drug addicted lying on filthy mattresses in the rubble-strewn streets. They

wanted to grow what they needed and remain comfortably situated on appropriated

picnic benches in community gardens. They wanted nothing more than to groove

with long term residents to salsa blaring from the boom box, dig through

mountains of used paperbacks resold on street corners and rediscover favorite

reads. They wanted an end to the war zone, the razor wire that separated

encroaching condos to be taken down, to take charge of their own safety. Graffiti

as legend: NO POLICE STATE, PROPERTY OF THE PEOPLE OF THE LOWER EAST SIDE.

This land was theirs and it was not for sale to the highest bidder.

Beneath

the angry pulse of helicopters they’d

linked arms in a human chain and passively resisted cops in riot gear. They faced

down the sniper, the automatic weapons and the tear gas. What

they got was an armored tank rolling up their street.

“Is

the Umbrella House still there?” Gaby asked.

The

building with a leaky roof—another raided of its inhabitants—became a celebrity

of sorts after a judge ruled in favor of the squatters who then paid a dollar

each and returned to their apartments. The umbrellas that had been required

indoors gravitated to the fire escapes of the renovated building in a quirky,

decorative homage.

“Uh

huh. I think they pay rent to the city now. I’m not sure. The umbrellas are

long gone.”

Their

conversation, as always, revolved around transformation. It was happening on

the Upper East Side now. Spanish Harlem was getting to be less Spanish, less

Harlem.

“How’s

the subway construction going?” Dina asked. She’d expected a rant and got

merely a shrug. After the hurricane in November that hit lower Manhattan like a

bomb and crippled everything below 34th Street, Gaby carped less

about interminable construction on Second Avenue, sensitive to her friend who’d

suffered pitch black freezing nights, cut off from everything, for five long

days. Manhattan

had always seemed impermeable. Maybe not so much anymore.

When

Gaby’s building downtown was demolished, she’d had no recourse but to move. Even

fifteen years ago rents were out of her reach and she’d called it quits. Newcomers

were heartless, she said. The neighborhood was changing too quickly. Streets

were quiet midweek, its defectors somewhere else making the kind of money that

afforded the new narcissism. On weekends, crowds funneled through the area like

they were at a heritage theme park, marveling at the metamorphosis of the

clutter of rag and bone into spare, high-end style clothes emporiums. Sports

bars, once unheard of in that part of town, spilled rowdy fans into the streets

at every big game. Artisanal cocktails took out cheap beer and live music. The garrulous

brunch crowd today resembled a juiced up fire sale.

Affordable

brought Gaby to the walk up on First Avenue and the hackneyed jokes about

nosebleeds from her old downtown friends. Until they, too, had to join the

artists’ migration farther north and resettle in neighborhoods like Washington

Heights and Inwood.

Dina

hung on. She’d made it through sweltering summers made worse by arson. Cherry

pickers had craned throughout the neighborhood, searching for hot spots. But she

remained downtown. The death mask facade of a drug store chain appeared where

once the prow of a sailboat had jutted onto Avenue B from the wildly inventive

gates surrounding the Gas Station. Her friend, Osvaldo, had run the poetry and

music venue with an unflagging pursuit of the radical. It was her go-to place,

an extension of Osvaldo’s artistic life. He’d lived and painted in the tiny apartment

directly above hers until he died, nearly 25 years ago. Since then, her partner

in music and life, Mark Fairweather, had called it home.

Dina

had battled her landlord in court more times than she could count, but she

still had the rent-controlled apartment on 2nd Street. At her age,

she was in no mood to restart in another neighborhood. There were still pockets

of her kind downtown—fewer, but recognizable, nonetheless, by that urban twang

and a quick draw response like, “Fuck atta heah,” that suggested multiple

interpretations.

Nearly

eight years had passed since she’d lost natural light in a matter of weeks.

A

characterless brick building rose alongside her five-story tenement from the pitted

hollow of the community garden next door. It shouldered her building like a disagreeably

boring stranger in a cheap suit that would not be budged.

It

would have been easy to give in to the gloom. The neighborhood’s patron saint

of gardeners, Adam Purple, had lost the fight years before that and had watched

helplessly as bulldozers dismantled the Garden of Eden.

But

when the brick interloper was completed, Dina hooked up a timer and affixed daylight bulbs at

each of the three windows on the newly sunless airshaft. The lights shone for

twelve hours, from eight in the morning, and then the fairy lights kicked in. She

arranged fake plants in brightly painted window boxes. The bathroom window had

a built-in fountain. In the main window she’d installed a brass Buddha. This

went a long way to lighten her psyche.

Dina

and Gaby drank green tea and wolfed the coconut custard pie Dina’d brought. The

phone rang again. Gaby ignored it. “I don’t take this one. Vee talk. Any gigs

coming up?”

“Maybe.

Mark is thinking about it. Reforming—.”

“Vit

you?” Gaby asked.

“Yes,”

Dina replied, “But maybe only going out, just the two of us.”

Dina

had removed herself from public performance. She’d been singing and playing guitar

for over forty years. She’d needed a break and she’d taken one.

“I’ve

been working on some new stuff, personal songs, but more abstract. Maybe, just

with Mark on bass?”

“You

should. You let me know. I come see

you.”

Gaby

had not been downtown in some time. Compromised mobility and irregular income cramped

her style. Her graphic novels—limited edition masterpieces once prominently

displayed on the shelves at Printed Matter in SOHO, and now only available on

her website—still brought buyers from Japan, hungry for folk lore of the Lower

East Side. She had finally resolved to sell off her formidable Barbie

collection on eBay.

“I

vas just being stubborn, you know? My mom never let me have a Barbie. She was

right, but I didn’t know it then.”

Now,

apart from her physical discomfort, she seemed content with her cats among her

collection of vintage wind up tin toys. She crafted fanciful knitted cat toys for

consignment in local pet shops. She’d branched out into children’s dolls.

“I

make more tea.” Gaby struggled from a chair, waving off Dina’s offer to help.

“It’s good for me to move.” She made her way to the tiny, compact kitchen. “How

about you and Mark? I haven’t been down there since before Sandy, even.”

Gaby

stopped in the doorway, turned and covered her mouth with her hands. “Oh my

God,” she cried. “I chust realized. Your sister’s name is Sandy! How perfect is

that?”

Dina

shook her head, laughing: “Good one, Gab.”

“So,

Dee, what’s with your sister? When was the last time you saw her?”

“You

remember,” Dina said. “I think twelve, maybe fifteen years ago, maybe longer.”

Dina looked up from her tea. “Um, she faked cancer?”

She’d accommodated Sandra

Grace as much as she could stand, imagined that sibling simpatico would

eventually materialize. Dina had once invited her for a weekend visit. Dina

stayed with Mark. She’d returned the next

morning to see her studio trashed, her sister gone. Dina learned that lesson

and never again allowed her sister to be alone in her apartment. Changed the

locks. Guitars were far too dear to replace.

“All mouth and no

trousers,” Mark said. But that was the last time he had anything to do with

her. Dina had persisted until the cancer.

“Ya

ya, I remember,” Gaby groaned. “You don’t see her for a long time before that. I

remember you telling me she used to keep a neck brace in the trunk of her car.”

“That’s

right,” Dina cracked. “Just in case she had to sue someone for her own crappy

driving.”

Gaby

shouted from the kitchen. “Four husbands now? Vaht a lunatic.”

Dina

followed Gaby and leaned in the doorway. Four husbands and Dina hadn’t had one.

Once, nearly, many years before she’d met Osvaldo. She had just turned 21. Marriage

was proposed after an unexpected pregnancy. Abortion was still illegal in New

York. She’d rejected marriage and took her chances.

Even

Mark had been married, just not to her.

At

the door Gaby thanked her for bringing groceries, picking up her laundry, saving

her a laborious trip down and up four flights.

“Give

my love to Mark. You’re an angel.”

“You’d

do the same for me,” Dina said, hugging her.

“Ya,

ya, of course.” She handed Dina her jacket and scarf. “That vas Osvaldo’s,

right? You still have it. Nice.”

* * *

“We are being held here in the station due to

train traffic ahead. We should be moving shortly. We are sorry for any

inconvenience.”

Dina,

still thinking about Osvaldo, jerks from her reverie.

Stalled

again at 68th Street. How long have they been in the station? A live voice over

the PA system is a rarity these days. And the spiritless intonation of the

recording is not even close to a real New Yorker’s voice, which has nothing

neutral about it. A man sitting across from her mumbles to no one in

particular: “They don’t ask us to be patient any more, at least.”

Osvaldo

had once been the great love of Dina’s life, no doubt. He was a downtown

fixture, avant-garde impresario. They were inseparable. He never understood why

she chose the Country Western route, but he dug her let’s-fool-around hairdo,

the whole Loretta Lynn thing, as he called it, and he loved rummaging at Cheap

Jack’s with her, dressing her for gigs.

He

did once ask her to marry him, for the green card, and she’d wished she had.

When he died in ’88 she’d risked months of bourbon-fueled, grievous sexuality.

While

on tour, a year after that, she’d met Mark at a bar in San Francisco. Originally

from London, he was dismantling an American marriage with liberal pints of

Guinness. He was a bass player in a rock band whose claim to fame had been a gig

in San Quentin playing, as he’d put it, to a captive audience. He’d been to New

York. He knew a lot of the places she did, played in some of the same venues.

Offstage

and dressed down, she’d recounted stories of her life in Manhattan, about

Osvaldo and the Gas Station, the Nuyorican poets and the once fabulously

pervasive Gay scene that was still reeling from the epidemic.

“I’ve

lived in the Haight for ten years,” he’d told her. “I know.”

Animated

banter about her neighbors made him laugh: Johnny Ramone, in head-to-toe black,

tripping down the front stairs of his building, forgetting the count midway and

having to do it all over—again and again. Mark cheered at the news that Quentin

Crisp and his lavender chapeau had left England, lived around the corner from

Dina. He knew of those community gardens.

Intrigued,

and hardly put off, he listened raptly as she described warehoused apartments

that turned into crack dens, coming home to a spaced out junkie huddled in the

shadows, the front door lock perpetually broken. Dina mimed the superintendent

in her building, a well-baked, thickset Polish lady in her 70s who’d swing a

baseball bat, hollering: “Get da fuck outta my building!” When the freak was

routed she’d mutter, “Got a piece of it.” Dina told him about the dealers who yelled

“Goya!” when the lookouts at the end of her block signaled the all clear and

moved the line of users closer to a hole in the wall of the abandoned building

across the street. How, before they recognized her as a tenant, they’d yell at

her to “Get in line, Bitch!”

“Shooting

galleries?” Mark had asked.

“I

don’t know, maybe…” she told him, “…too scared to find out.”

Mark

was easily persuaded to Dina’s show in The Mission. Afterward, his reaction was

surprisingly swift and furious. Rhinestone studded cat eye specs? Shit kicker

cowboy boots? A beehive? She had a

great voice, but why the fuck was she channeling dead country, calling herself

L’il Dee?

She’d been too long in the music she’d chosen for

her safe place.

Her father had offered what he could, always

wrapped up in the problems of boys who would be in jail, if not for the band. Dina

ignored her sister’s wisecracks when she caught Dina in the bathroom with the

transistor radio, mirror-singing to girl groups. There was gonna be ‘one fine day’

but it was gonna be considerably ‘easier said than done.’

Among

Dina’s classmates, one girl had already had a hit tune recorded by a popular

group. Dina’s best friend, Dorrie, raced up the steep hill from Jerome Avenue every

day after school to catch American Bandstand on the TV. Dina headed downtown

and across the East River, the same river her nephew would ceremoniously toss

every photo he had of his mother before he set out for the West. When she’d alighted

at her stop in Astoria she’d listen for the canorous chorus of a doo-wop group

that greeted her like the voice of an old friend

Only you can make

this change in me…

It

never failed to echo her desire.

It had taken nerve to put her out there. To single

handedly insert herself in the scene. She’d fallen into Country to be

different. Mark’s reaction reminded her she’d grown tired of that cheerful,

knee-slapping stage presence.

“How is it you’re not a lot grittier?” Mark had

asked. “You’re a native New Yorker. You must

have stories, for fuck’s sake!”

He’d offered a conciliatory gesture to her pained

expression. He told her about winning a bet with Bleecker Bob in his famed

record shop. Challenged to name a band he didn’t have on vinyl, Bob had lost

the bet to Van Der Graaf Generator, the Pawn Hearts album.

She’d

laughed for the first time in a long time. She fell in love. She fell hard.

Mark

followed her to Manhattan, maneuvered his gear down a dimly lit, impossibly

narrow hallway like a tomb raider. He’d stuck in with her in her suddenly

claustrophobic apartment for a few months until Osvaldo’s old apartment opened

up. They formed a songwriting partnership and eventually, a band. They were

both together and separate and it suited them.

The

doors crimp a lanky, ragged tree limb of a man forcing his way into the subway car.

His scalp is shaved, his skin darkened by circumstance. There is loathsome

hilarity in the man’s grin. His teeth shear the air. His arms fling about with

prophecy.

“God

is saying to all the ladies: “Long coats, ladies!” He veers from wary passengers.

“I tell Satan to get thee behind me.” He

turns his fury to the young woman who had been dancing and Dina is relieved he

had not shown up earlier. “The men lust after you every time you wear short

coats. You will go—.”

Bible

lady shushes him. Another passenger carps, more forcefully, that nobody cares

about his stupid rant, that he is no goddamn saint. This only increases the

man’s caterwauling.

Knots

of passengers disembark at 59th Street. The arrival of a trio of

Mexican musicians sends the preacher scurrying to the next car.

The

train edges slowly out of the station. It bangs to a halt in the tunnel. The musicians—celebratory

and loud—quit after a few thumping beats. The trio heads to an adjoining car. Dina

is not all that sorry to see them go. Still, she places a dollar in a black

Stetson as they pass.

“They

are doing their best, just like us,” Mark would say.

Dina

had felt, for some time, like she wasn’t doing her best. That’s why she stopped.

Mark had been put out, at first.

“It’s

what we do,” he said. “We write songs. You sing them.”

But

Dina needs to stretch. They have been in a comfortable place for more than

twenty years, too comfortable. It seemed like every song they wrote became a

kind of love song. They had—still have—stories. All those years on the road together—but

she is on an inward course now, and she wants to see where it takes her.

She,

quite simply, is ready to tackle the dark side.

Her

idea is to incorporate spoken word, sing as she sees things in a bluesy Annette

Peacock kind of way: grief in the newly homeless, dignity in the more enduring,

how she found pleasure in the details and pain in the big picture. Never having

flown too high she doesn’t have too far to fall. She wants this. Mark’s

resistance gradually gave way to the cheerleading that suited him.

“Let’s

do it,” he said. “We can do whatever we like. As Randy Burns always says, “Folk

rap has not been invented yet.”

She

doesn’t read on the subway so much as she used to. She likes to know what’s

going on, listen to conversations. Dina slips a small spiral notebook from her

jacket pocket. Before this news of an impending marriage the only time she’d

thought of her sister came at natural and very unnatural events that inspire

those out of touch to reach out, like the hurricane in November and 9/11 before

that. Her sister had not reached out and for that Dina was grateful.

“Some people lack the

guilt gene,” she writes. “Sandy dismembers it.”

The last time Dina saw

her sister was in Connecticut, another attempt at reconciliation. At the time

Sandy was between husbands.

Sandra Grace had headed

straight for Connecticut right out of high school. She hated where Dina lived

on the Lower East Side. Seedy, she’d called it. Her neighbors were gross. Plenty

of opportunity in the insurance capital of the world, she boasted. She’d

bounced around Hartford and husbands—until she found the ‘home of her dreams’

in a gated community of colonial brick townhouses in Farmington. She had a pool

and a tennis court and neighbors who believed in rules.

“Decorating

is my life!”

Dina

remembered her sister’s exclamation, and then spluttering into her drink on the eve of Sandy’s

supposed surgery for a non-existent cancer. They’d had cocktails on the little

stone patio, eerily surrounded by scowling plaster gnomes.

The patio faced a

Cimmerian wood, which Dina was sure crawled with characters from the pages of

Stephen King and a mushrooming dread. Still, it was better outdoors than in the

screamingly ostentatious interior. The

visit was a disaster. A lie, meant to draw Dina back after yet another falling

out, had finally caused the irreparable rift.

Dina writes furiously,

describing her sister as a child, the explosive tantrums. She was the little girl

with a loose pin, the world’s angriest dog.

Dina notes that her first

guitar met its fate when Sandy accidentally dropped it from the third floor

window of their shared bedroom in the projects.

And then, Dina remembers

the kitten.

Their grandmother was the

superintendent in a run down building off Steinway Street in Astoria. Dina and

her sister were fascinated with the coal cellar, and heedless of the filth, scrabbled

around in the black pit looking to unearth treasure. She must have been six or

seven when they discovered a litter of newborn kittens, mewling and still

blind. Their grandmother swiftly gathered the brood into a pillowcase. Sandy’s

relief turned to horror when she realized they would be drowned. She’d screamed

with a force that shocked her grandmother. Dina pleaded with the old woman not

to kill the kittens. Disgusted and bemused, their grandmother removed the

tiniest of the squirming bunch and handed it to Sandy who promptly named it

Joe.

At home she was shown

how to feed the kitten with an eyedropper filled with milk. Sandy had anxiously

cupped the frail body. “Gently, gently,” her mother prodded in a voice burdened

by impatience. She took the kitten from

Sandy and handed it to Dina. “You try.”

Sandy’s cheeks swelled

into angry red blisters. “Mine!” she’d shrieked.

“No,” her mother said. “Share.”

With the force of a miniature

cobra, Sandy’s small hand struck out. Trembling with rage, she held the kitten

high above her head of tender blonde curls and flung it to the hard kitchen

floor.

Dina shivers as the train

jerks to life, remembers staring in sorrowful fascination at the lifeless

handful of fur.

The train cranks into 42nd

Street. Dina catches sight of a familiar, nervy little guy on the platform as they

pass. Delays are announced. Train traffic ahead. Agitated passengers head for

surer routes home.

The

last Doo Wop guy, the one she recognizes on the platform, the one she still

sees occasionally. There had been four of them once. Over the years their

quartet has dwindled. Dina recalls, with a start, the time they saved her.

It was her sister’s first

marriage. Months before that Dina had confessed to an abortion. Sandy could

still change things, Dina urged her. She didn’t have to marry the deadbeat.

“I

am having this baby,” Sandy insisted.

There

was no church wedding. The reception unraveled in the Shipwreck Lounge of a

Greek diner on Farmington Avenue. Relatives and friends on both sides went to great lengths

to ignore the burgeoning life under a milk froth of lace. Sandy ignored her new

husband and made the rounds, her satin purse gaping, like she was collecting a

debt. Dina’s mother was an overdressed

turbulence that sent everyone to the bar, including Dina.

Drunk

as she was, Dina had the sense to turn down her cousin’s offer to drive her

back to Manhattan. They had been guzzling Martinis since the “I dos”. “Don’t

leave me with them,” he’d pleaded. Somehow she made it to the Greyhound station

in Hartford. She remembered nothing about that bus ride except the driver’s

name was Ernie

Budlong, and the sign above him promised he was safe, courteous and reliable.

She’d

landed quite alone on the subway platform at Times Square. Four Black men had approached

her. They surrounded her. She’d roused and articulated a fury at everything

alcohol had dimmed. They responded with perfect Doo Wop and an a cappella

harmony that enveloped her like angel wings.

She

hears him rushing through why fools fall in love before he stands before her,

flat cap in hand. Dina looks up at his now toothless grin.

“Hey,”

he says. “I know you.”

“I

know you.” Dina returns his smile and lands a fiver in his outstretched cap. He

hops off at 14th Street followed by the dancing girl and her friends.

Dina

decides not to transfer to the F at Bleecker and exits on to East Houston. She

can still catch up with Magic Man at the National Underground. He’d promised to

revive his straightjacket escape routine. Nelli McQueen will be there. Dina

will ask Nelli about booking her and Mark again. She’ll start to explain that

they are doing something very different and Nelli will interrupt, flash a smile

of pure warmth, and say: “Anything you do is alright with me Darlin’”.

It’s

a balmy, dark night and the walk will do her good.

For GB who somehow survived the storm

Heartfelt thanks to

Beatrice Schafroth and Diego Semprun Nicolas

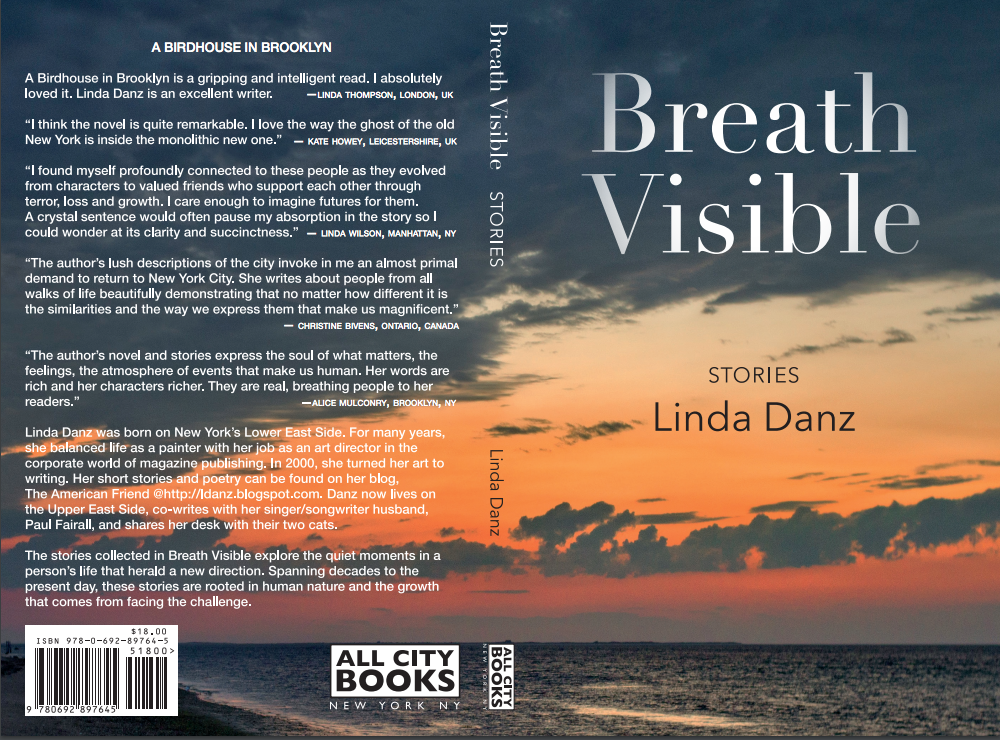

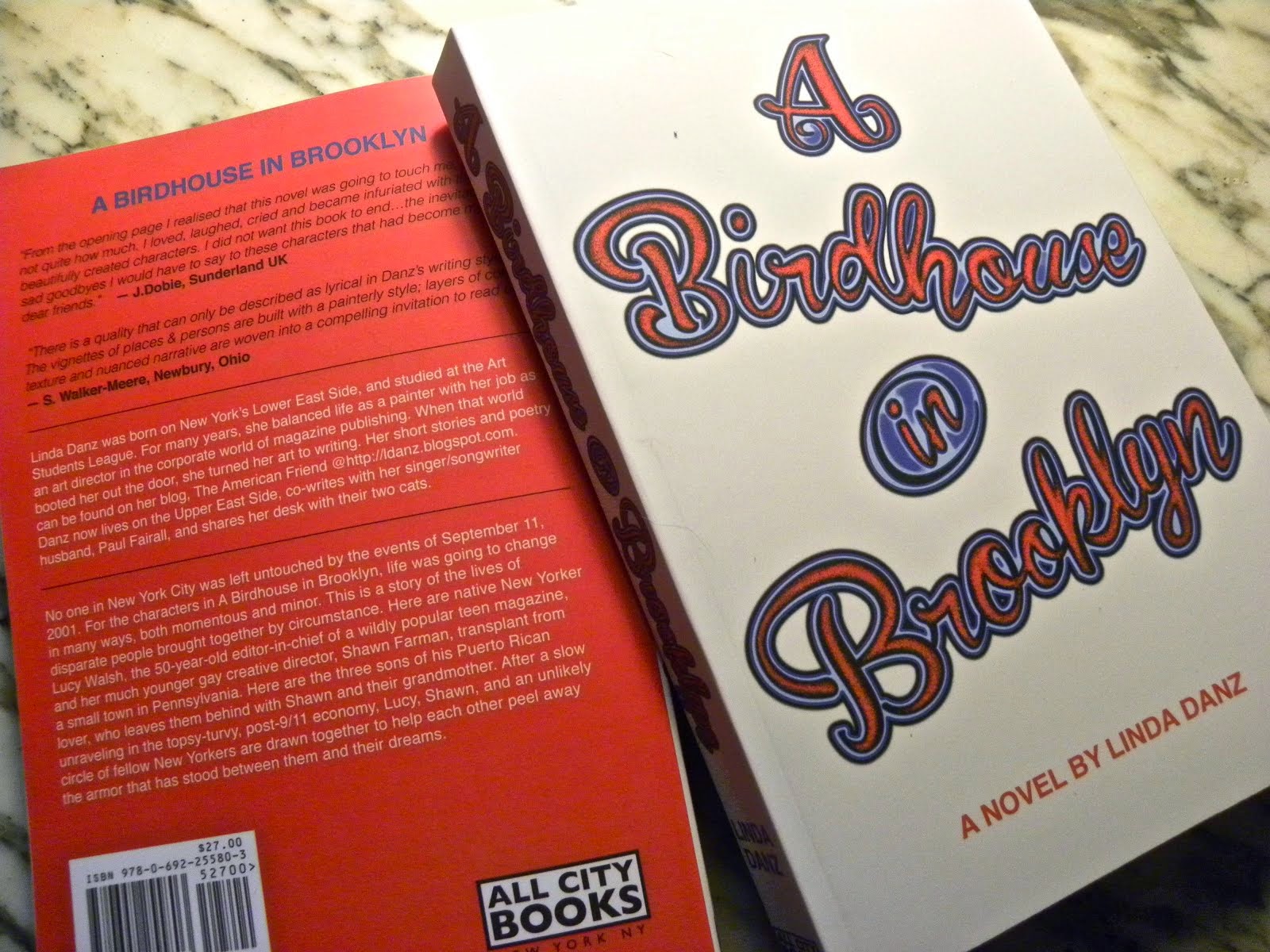

SAINTS

AND ANGELS is an original short story by Linda Danz.

STORIES

ON THE AMERICAN FRIEND Writers Guild of America, East #R28299

This is a

work of fiction. Names, characters, business organizations, places, and

incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or used

fictitiously. The use of names of actual persons, places, and events is

incidental to the plot, and is not intended to change the entirely fictional

character of the work. © JUNE 2013.